By John Baeke

The history of automobile manufacturing in America, especially during the first half of the 20th century, is marked by a roller coaster of successes and failures.

During the mid 1920s, under the direction of Alfred P. Sloan, General Motors rapidly became a corporate juggernaut. Its conglomeration of two dozen brands of cars and trucks far outpaced Ford. Of the 3,000+ manufacturers once producing motorcars in the U.S. (you read that right), only a handful would survive the recession of the early 1920s, the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Second World War of the 1940s.

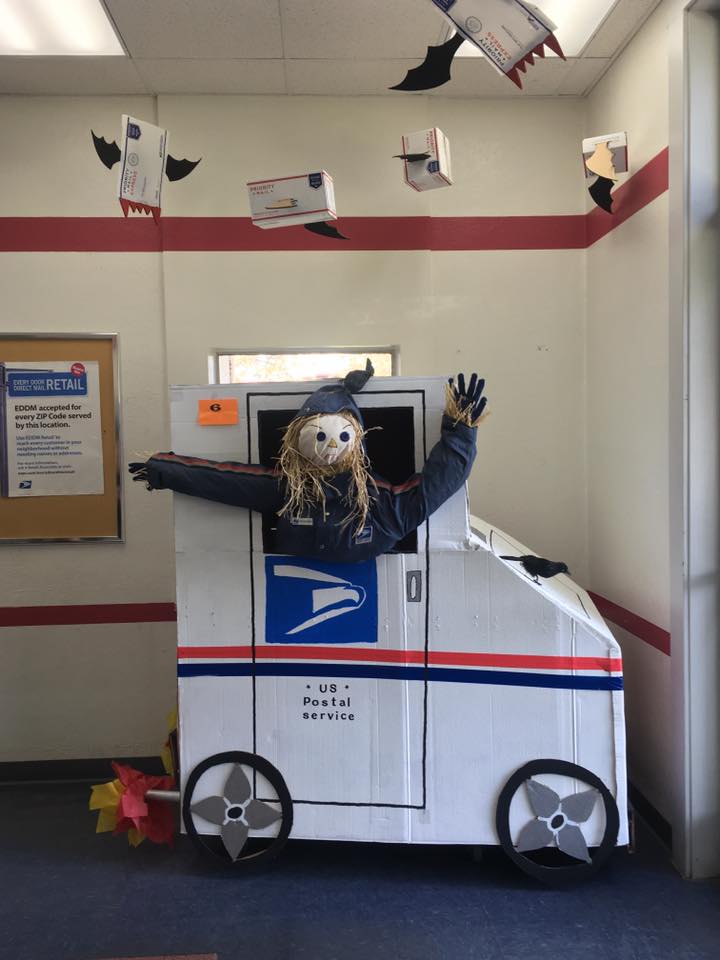

Designers’ art as they attempted to join the “jet age” while still paying homage to Chief Pontiac.

Even mighty GM felt the sting. Between 1928 and 1932, sales of GM vehicles plummeted by about 80 percent, from 2.7 million to 522,000. Few folks could afford the luxury of a new car, many making do with a patched-up Model T.

GM instituted all manner of cost-cutting measures. Several of its brand names were euthanized — Marquette, Viking, Oakland and LaSalle — names which today only avid old car buffs know. Choices of models were limited. It was no coincidence that Chevys, Pontiacs and Olds looked quite similar.

The mantra GM passed onto its dealerships was, “Break Even OR Go Broke.” In 1932, GM somehow remained profitable, but net income was a mere $164,979!

All of the manufacturers of the day realized that until happy days returned, most new-car buyers would settle for the practicality and economy of sedans, especially those with thrifty 4- and 6-cylinder motors, rather than the more powerful and expensive eights. Yes, GM divisions did offer snazzy two-passenger hardtop and convertible coupes (aka cabriolet). But their higher expense and frivolity made them mostly the objects of little boys’ dreams, not the choice of the working class. Thus few were built and fewer survive.

The new brand for 1926 was Pontiac, which was positioned in the mid-price range. It enjoyed immediate success. Pontiac-Oakland sales hit 244,584 in 1928. But that was the year before Black Thursday and the crash of 1929. From thence forward, Pontiac sales slid, hitting bottom in 1934 at 78,859, ranking seventh among carmakers.

Sloan made the bold decision to hire a young automobile designer, Franklin Hershey (of Beverly Hills), to work under Harley Earl in GM’s new Art & Colour Section.

Hershey had already made a reputation designing custom bodies for Duesenberg. One of his first assignments was to re-invigorate the failing Pontiac line. Some flair was needed. As Earl was a proponent of the Art Deco influence (designs using geometric shapes and parallel lines), his new protégé followed that trend.

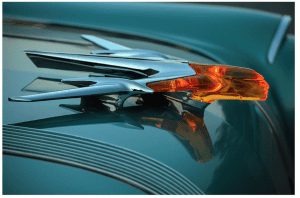

The Art Deco ornament on the ’36 8-cylinder cabriolet shows how dramatically different Franklin Hershey’s designs could be.

What Hershey penned would become the iconic symbol of Pontiac for the next 22 years — the Silver Streak. Capitalizing on the public’s fascination for streamlined trains, the styling motif that would adorn Pontiac involved several shiny chrome stripes running down and over the hood. This simple bit of bling not only gave Pontiac a splash of style —completely unlike its corporate brethren, Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac — but heralded new model names, which too evoked sleekness and speed: “Silver Streak,” “Dual Streak,” “Speedline,” “Torpedo,” “Silver Arrow” and “Super Streamliner.”

In a time of financial blues, Hershey’s touch was gold. To quote one reporter at the New York Auto Show, New York City “has literally taken to its bosom the new Pontiacs when the doors opened.” During the first year of the Silver Streak (1935), Pontiac production increased from 79,000 to 179,000, improving their ranking from seventh to fourth.

Encouraged by public enthusiasm and corporate nods, Earl and Hershey every year created a new silver streak motif. Eventually the waterfall of chrome and polished aluminum would extend all the way from the front to rear bumpers.

What is equally intriguing for aficionados of automotive design is the masterful manner in which the two men were able to honor the brand’s namesake, Chief Pontiac, by blending in the Indian’s head, or even full body, yet stay true to the Art Deco elements. Every year, these designers created two different styles of silver streaks with Chief Pontiac mascots — one for the models with 6-cylinder motors, and a separate one for those with 8-cylinders.

Over the years, the Indian took on many shapes. The two Pontiacs pictured with this column show a couple of extremes. The 1935 Cabriolet-8 features a very anatomically correct Indian squaw, while the 1936 Cabriolet-8 has a most abstract mascot, barely recognizable as being Indian.

With every new model year, the mascot and silver streaks became more ornate. In the 1940s, the Indian wore elaborate headdresses, made of amber, red or green Lucite, and illuminated to glow at night.

Come the dawning of the jet age, 1950s Pontiacs had Indian mascots actually sprouting airplane wings.

Just weeks before introduction of the 1957 models, a new general manager was seated at the helm of Pontiac, Bunkie Knudsen.

Noting that Pontiac sales were again lagging, and believing the Pontiac mascots had become whimsical if not ridiculous, just weeks prior to release of the 1957 models, Knudsen forever removed the silver streaks and Chief Pontiac mascot that had proudly ridden atop the line of cars since 1935.

On a recent warm night, two rare Silver Streak Pontiacs — a 1935 Cabriolet-8 owned by JoAnn and Bob Kauffman of Nipomo and a 1936 Pontiac Cabriolet-8 owned by Olivia Baeke of Solvang — met at Michael & Christina Larner’s Los Olivos General Store. This wonderfully preserved building was formerly the Rice Bros. Garage (circa 1903). History lives!